TransLash Media’s Black trans-affirming Black History Month guide was originally published in 2022. We update our guide annually in February; bookmark this page to explore even more inspiring stories about Black transcestors, living icons, and pioneers.

Produced by Daniela “Dani” Capistrano, with 2024 additional reporting by Zarina Crockett

Black trans people have always been here; breaking through barriers and creating new possibility models for everyone. We at TransLash uplift Black History Month to celebrate the prismatic range of Black trans legacies and to remind the world that there is no liberation without Black trans liberation.

BLACK HISTORY MONTH: TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. ‘Negro History Week’ Origins

II. Black History Month: Brought To You By Black Cis And Trans Scholars

III. Why Black Trans History Matters During Black History Month

IV. Black Trans People Are Indigenous

V. Black TGNC African Histories And Legacies

VI. Colonialism’s Insidious, Anti-Black Legacy

VII. What Is Trancestry / Transcestry?

VIII. Black TGNC Trancestors / Transcestors

IX. Black Trans Living Icons And Pioneers

X. Black Representation In Media

XI. Black Trans Actors & Black Trans-Led Media

XII. Black Trans Politics & Activism

XIII. Black Trans Lives: 2022 and Beyond

XIV. Black Queer & Trans Reading List

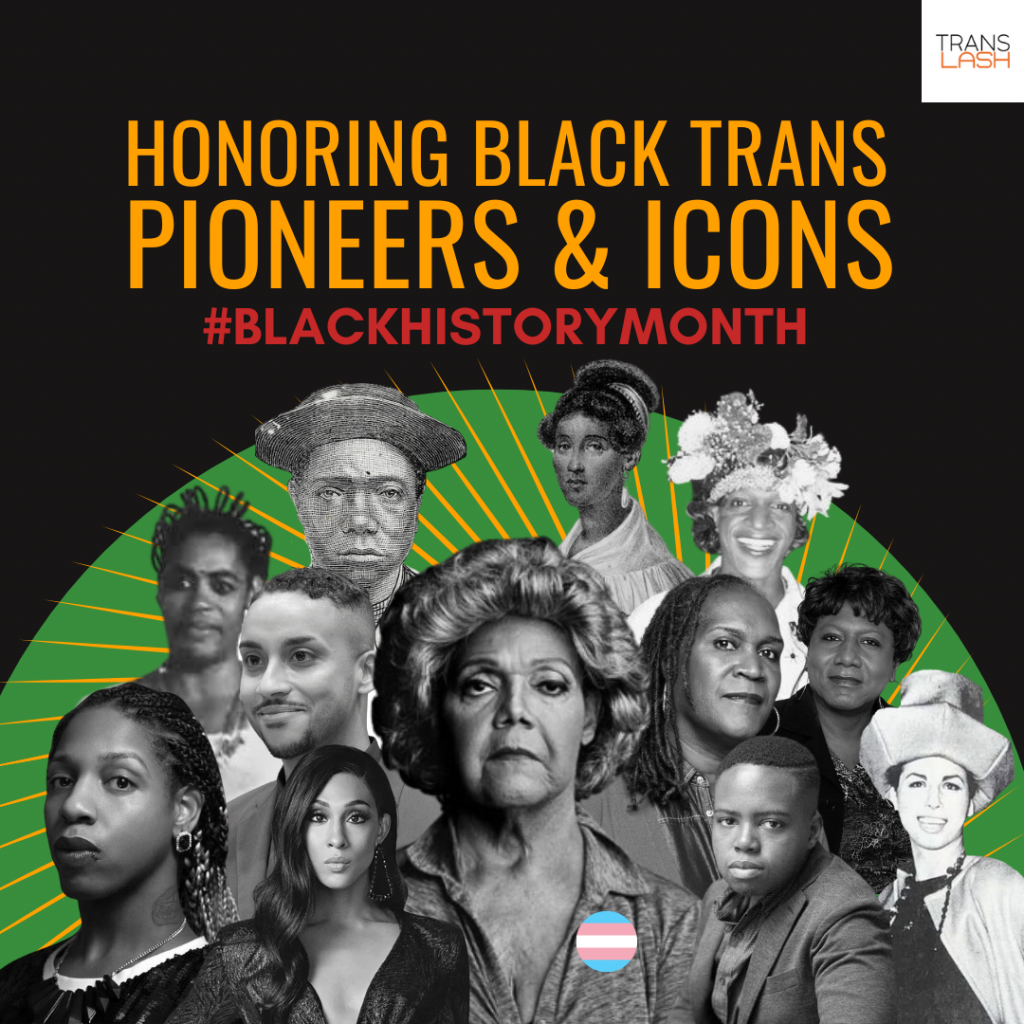

Black History Month’s ‘Negro History Week’ Origins

In 1926, historian Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) announced the second week of February to be “Negro History Week”. This week was chosen because it coincided with the birthday of Abraham Lincoln on February 12th and that of Frederick Douglass on February 14th, dates which Black communities had celebrated together since the late 19th century.

In 1915, Woodson had participated in the Lincoln Jubilee, a celebration of the 50-years since emancipation from slavery held in Bronzeville, Chicago. The summer-long Jubilee drew thousands of attendees to see exhibitions of heritage and culture, inspiring Woodson to draw organized focus to the history of Black people. He led the founding of the ASNLH that fall.

At the time of Negro History Week’s launch, Woodson emphasized that the teaching of Black History was essential to ensure the physical and intellectual survival of the race within broader society:

If a race has no history, it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.

Negro History Week grew in popularity throughout the following decades, with mayors across the United States endorsing it as a holiday.

Black History Month: Brought To You By Black Cis And Trans Scholars

Black History Month was first conceived of by Black educators and the Black United Students at Kent State University in February 1969. The first celebration of Black History Month took place at Kent State from January 2 to February 28, 1970.

Six years later, Black History Month was being celebrated all across the country. President Gerald Ford recognized Black History Month in 1976, during the celebration of the United States Bicentennial. He urged Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history“.

In the Black community, Black History Month prompted the creation of Black history clubs, an increase in interest among teachers, and interest from non-Black allies.

On February 21, 2016, 106-year Washington, D.C., resident and school volunteer Virginia McLaurin visited the White House as part of Black History Month.

When asked by President Barack Obama why she was there, McLaurin said: “A Black president. A Black wife. And I’m here to celebrate Black history. That’s what I’m here for.”

Dr. C. Riley Snorton, a Black trans scholar, author, and activist, researches and shares knowledge that focuses on historical perspectives of gender and race, specifically Black transgender identities.

Snorton‘s publications include Nobody is Supposed to Know: Black Sexuality on the Down Low and Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity.

Listen to Imara discuss trans history with Dr. Snorton on TransLash Podcast with Imara Jones:

Dr. Snorton is just one of a growing number of Black trans people who are documenting and stewarding Black trans histories for the world to discover and share.

Learn more below about Black trans pioneers and icons:

Why Black Trans History Matters During Black History Month

When we celebrate Black History Month, it is important to remember that we are equally celebrating the lives and legacies of all Black people: transgender, cisgender, and gender nonconforming.

Black Trans People Are Indigenous

The diverse tapestry of Black transgender history is rooted deeply in Indigenous cultures. Long before Western contact, many Native American tribes recognized and revered Two-Spirit individuals.

Two-Spirit people embody the essence of both masculine and feminine spirits, playing vital roles in their communities.

What we know is that Black trans & Two-Spirit Indigenous people also play a significant role in helping to unpack and heal anti-Blackness that lingers in some Indigenous communities, while also educating LGBTQ+ communities about Indigenous issues and resources.

M. Carmen Lane, a “two-spirit African-American Haudenosaunee artist and consultant,” shared the following guidance with Autostraddle in 2020:

“Two-Spirit is a shorthand, because it’s an English translation. It’s more like two ‘worlds’ or the totality of creation. So when someone says they’re two-spirit, it doesn’t mean half man/half woman or both man and woman. It’s like I’m male and female and not male and not female and I’m a man and I’m a woman — it’s all of these things that bridge space and time, because who we were and are and continue to be has been molested by colonization.”

We at TransLash celebrate the enduring legacy of Two-Spirit identities, through which we also gain a deeper understanding of the historical and cultural significance of Black trans and gender nonconforming people in the tapestry of human history.

Black TGNC African Histories And Legacies

When we talk about Black History Month through a trans lens, it’s important to ground ourselves in what informs the identifies and cultures of the global African diaspora.

Historically, gender in African societies did not adhere to strict binary gender norms before colonialism took hold. For example, the Langi people of northern Uganda recognize mudoko dako “effeminate” males who lived as women and could marry men.

Here are other queer and trans African diaspora examples that warrant a deep-dive:

- 📖 Woman-to-Woman Marriages: Documented in over 40 African societies, these marriages allowed a woman to take on the role of a husband, challenging gender norms. This practice was prevalent across various cultures, indicating a different approach to gender and marital roles compared to Western norms.

- 📖 The Chibados and Quimbanda: In Angola, male diviners known as Chibados or Quimbanda were believed to carry female spirits, demonstrating the existence of gender-variant roles in African spiritual practices.

- 📖 Queen Nzingha Mbande (Angola): Ruled in the 1600s and exhibited gender fluidity, being referred to as “King” and taking on roles traditionally assigned to men, such as leading troops in battle.

- 📖 King Mwanga II (Uganda): Openly gay or bisexual, Mwanga II resisted British colonial influence and represents pre-colonial lives of diverse sexual orientations.

- 📖 Area Scatter (Nigeria): A gender non-conforming musician in the 1970s, she challenged gender norms through her artistic expression and performance.

- 📖 Simon Nkoli (South Africa): A prominent anti-apartheid and gay rights activist who played a significant role in advancing LGBTQ+ rights in Africa.

Colonialism’s Insidious, Anti-Black Legacy

Anti-Black laws and societal norms imposed by colonial powers drastically altered the landscape of gender and sexuality in Africa and the global African diaspora. The homophobia and transphobia still prevalent in some contemporary African societies is in fact remnants of colonial influence, reinforcing harmful propaganda that gender diversity is “un-African.”

In pre-colonial Africa, gender was not always a primary organizing principle. For instance, among the Yoruba people, gender roles were not strictly defined, and women held positions of prominence and power in society. Women were involved in politics, trade, and were key decision-makers in their communities.

In Ghana, queen mothers in the Asante culture were part of a dual-gender system of leadership, holding significant authority alongside tribal chiefs. Similarly, Yoruba women were central figures in long-distance trade and could hold the chieftaincy title of “iyalode,” signifying considerable power and privilege.

@donnellwrites Colonialism in the spread of Christianity in Africa, Part 2. Original video: @Stuart Knechtle Part 1: @@donnellwrites The original video here highlights a very common myth that Christianity spread in Africa because of Ethiopia. It’s a lie told to dismiss the legacy of European colonialism which is the primary reason for the spread of the Christian faith in the land of my ancestors (West and Central Africa). Let’s talk about it. In this portion I highlight some resources for folks to look into that debunks more of this misinformation, and that sheds light on how African religious practices survived the Middle Passage. Like, comment, and share to boost this important message 🎙️💬 #blacktiktok #africa #decolonize #blackhistory #exvangelical #spirituality #ancestors — Check out the link in my bio to sign up for the 5 month Virtual Ancestral Elevation retreat; I’ll be there teaching on white supremacy and the demonization of ATRs with @DorothysHouse ♬ original sound – Donnell

The arrival of white supremacist colonial tyranny in Africa introduced patriarchal structures and binary gender norms that significantly devalued the roles and contributions of women, leading to a dramatic reshaping of family structures and gender relationships.

This enforcement and threats of European norms, policies, and laws drastically reduced women’s influence and power, especially in public and political spheres, relegating them to subordinate roles and causing a significant loss of their earlier societal status.

Additionally, European colonizers, influenced by their own cultural biases, often condemned and criminalized non-heteronormative sexualities and gender expressions.

Historical accounts, such as those of Francisco Manicongo from Central Africa, highlight the oppressive colonial attitudes towards gender and sexual diversity.

These atrocities not only suppressed but also pathologized diverse gender expressions and sexual orientations, leading to the iimport of homophobia and transphobia into African cultures, contrary to the pre-colonial acceptance of gender and sexual diversity.

Despite centuries of attempts to erase, criminalize, and dehumanize Black trans people worldwide, today throughout the global African diaspora, there are many Black TGNC people who continue to fight for LGBTQ+ rights while centering Black trans voices.

Black trans people derive strength and healing from the legacies of our Black transcestors, learning from the ways they navigated their pockets of history to share their powerful stories, knowledge, and spiritual practices.

What Is Transcestry?

Documenting Black trans history and legacies is related to “transcestry” or “trancestry,” a concept credited to Black trans activist CeCe McDonald.

Transcestry is the practice of telling the stories of transgender people to honor their historical significance.

Transcestry/Trancestry is a term that is now embraced by many trans people and allies from all walks of life, all thanks to CeCe McDonald, a Black trans woman.

Black Trans And Gender Nonconforming Transcestors

When we celebrate Black History Month, it is important to remember that we should be equally celebrating the lives and legacies of Black TGNC people who cleared a path for all Black people who have faced oppression and tyranny.

Here are just a few of our Black transcestors to honor this month and year-round:

Mary Jones (1803 – 1853)

Mary Jones, born in 1803, lived her life defying the rigid gender norms of her time. Her arrest in 1836 was not only for “cross-dressing” but also involved other sex worker charges, consequently producing one of the earliest recorded instances of a Black transgender person in American history.

Despite the legal and societal challenges she faced, Mary Jones’ life is a testimony of death-defying class jumping, colorful creative indulgences, and the sensual existence of Black trans women long before the term “transgender” itself was coined.

Jones’ story offers us unique and early insight into the life of a transgender individual during the 18th century.

Frances Thompson (1840 – 1876)

Frances Thompson was a formerly enslaved Black trans woman and anti-rape activist who was one of the five Black women to testify before a congressional committee that investigated the Memphis Riots of 1866.

Thompson is believed to be the first trans woman to testify before the United States Congress about being sexually assaulted by white men. She spoke on behalf of herself and a cisgender woman who was also assaulted.

Ten years later in 1876, after a decade of being targeted for speaking out, Thompson was arrested for “being a man dressed in women’s clothing”, and died that same year. Even behind bars, Thompson never lost her fight, answering rude questions about her gender with “none of your damn business.”

Today, the Frances Thompson Education Foundation facilitates Black transgender and non-binary scholarship and advancement, through direct financial, written, and oral scholarship.

Frances Thompson stood on the shoulders of Sojourner Truth, a Black cisgender woman, who in 1851, in front of a crowd of mostly white cisgender women, demanded body autonomy & rights for Black women in her legendary speech “Aint I A Woman?” at the Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio.

Both Frances Thompson and Sojourner Truth fought for Black women long before the white feminist movement even considered Black women worthy of equal rights. While white women in the United States earned the right to vote in 1920, Black women and many women of color had to wait nearly five more decades to actually exercise that right.

Pauli Murray (1910 – 1985)

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland on November 20, 1910, the fourth of six children to nurse Agnes Fitzgerald and educator William Murray.

According to the Pauli Murray Center for History and Justice, Murray self-described as a “he/she personality” in correspondence with family members. For years, Murray requested – and was denied – testosterone injections and hormone therapy, as well as exploratory surgery to investigate their reproductive organs, believing that they may have been intersex and had undescended testis.

Later in journals, essays, letters and autobiographical works, Murray employed “she/her/hers” pronouns and self-described as a woman.

A member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Murray worked to end segregation on public transport. In March 1940, s/he was arrested and imprisoned for refusing to sit at the back of a bus in Virginia. In 1941, Murray enrolled at the law school at Howard University with the intention of becoming a civil rights lawyer. The following year s/he joined George Houser, James Farmer, and Bayard Rustin to form the nonviolence-focused Congress of Racial Equality.

In the early 1950s, Murray, like many Black citizens involved in the civil rights movement, was suppressed by McCarthyism. In 1952, s/he lost a US State Department post at Cornell University because the people who had supplied her references (Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall, and A. Philip Randolph) were considered “too radical.”

When Murray was alive, language about LGBTQ+ communities, gender expression, and gender was different than it is today. We don’t know how Pauli Murray would identify if they were living today or which pronouns Murray would use for self-expression.

Pauli Murray joined Betty Friedan and others to found the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966, but later moved away from a leading role because s/he did not believe that NOW appropriately addressed the issues of Black and working-class women.

In 1977, Pauli Murray became the first Black person perceived as a woman in the U.S. to become an Episcopal priest.

Pauli Murray died of cancer in Pittsburgh on July 1, 1985. Their autobiography, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, was published posthumously in 1987.

Marsha P. Johnson (1945 – 1992)

According to the Marsha P. Johnson Institute, Marsha P. Johnson was an activist, self-identified drag queen, performer, and survivor. She was a prominent figure in the Stonewall uprising of 1969. Marsha went by “BLACK Marsha” before settling on Marsha P. Johnson.

The “P” stood for “Pay It No Mind,” which is what Marsha would say in response to questions about her gender.

So much of our understanding of Marsha came from the accounts of people who did not look like or come from the same place as her. As transness is now more accessible to the world, introducing the Institute to Black trans people who are resisting, grappling with survival, and looking for community has become a clear need.

In this episode of TransLash Podcast, Imara Jones interviews the incredible artist, filmmaker, and scholar Tourmaline, whose passion for understanding trans histories is the singular reason the world knows so much about Marsha P. Johnson:

Access the full transcript of this episode here.

Willmer Broadnax (1916-1992)

Also known as “Little Axe,” “Wilbur,” and “Willie,” Wilmer was a Black trans man who moved to Southern California from Houston, Texas, in the 1930s with his brother to join the Southern Gospel Singers.

He and his brother later formed their own group called “Little Axe and the Golden Echoes.” Eventually the brothers parted ways and joined various other groups throughout their musical careers. In retirement, Broadnax continued to record new material occasionally with the Blind Boys into the 1970s and 1980s.

As Black trans blogger, writer, and transgender rights advocate Monica Roberts documented, there is a dispute as to when Broadnax actually died.

Various sources claim it was 1994, but the Untitled Black Lesbian Elder Project website asserts that he met his untimely demise in Philadelphia in 1992. He and his girlfriend Lavinia Richardson were arguing when she stabbed him on May 23, 1992, and he subsequently died on June 1, 1992. It was on the autopsy table that Willmer Broadnax was ultimately revealed to be a trans man.

Monica Roberts (1962 – 2020)

In 2020, TransLash honored Monica Roberts a Black trans blogger, writer, and transgender rights advocate. She was the founding editor of TransGriot, a blog focusing on issues pertaining to trans women, particularly Black and other women of color.

Roberts’ coverage of transgender homicide victims in the United States is credited for bringing national attention to the issue.

TransLash Media stands on the shoulders of Monica Roberts, and we at TransLash continue to honor Roberts’ legacy.

Black Trans Living Icons And Pioneers

Here are just some of the many Black trans elders who continue to inspire us today:

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy (1940s – present)

Miss Major is an activist who has fought for over fifty years for her trans and gender nonconforming community.

Major is a veteran of the infamous Stonewall Riots, a former sex worker, a mother, and a survivor of Dannemora Prison and Bellevue Hospital’s “queen tank.” Her global legacy of activism is rooted in her own experiences, and she continues her work to uplift transgender women of color, particularly those who have survived incarceration and police brutality.

Sir Lady Java: (1943 – Present)

Black trans entertainers were rarely represented in media prior to the 2000s, but we existed; Sir Lady Java is a retired entertainer and lifelong activist who successfully fought against an anti-crossdressing ordinance in Los Angeles in the late 1960s.

Born in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1943, Sir Lady Java, also known simply as Lady Java, emerged as a pioneering figure in the transgender community and the entertainment industry.

She embraced her identity from an early age, transitioning with the support of her mother.Java’s career spanned across various domains: she was a talented exotic dancer, singer, comedian, and actress.

In the 1960s, Java faced discrimination due to Rule Number 9, a Los Angeles law that restricted drag performance. Her fight against this law marked her as a transgender rights activist and a pioneer in the struggle for equality.

In 1976, Java portrayed herself in the Dolemite sequel The Human Tornado. For decades, she continued to bring Black trans representation to the public sphere. In 1978, Java performed with Lena Horne at a birthday party for nightclub owner and columnist Gertrude Gipson.

Lady Java was also one of the first transgender people to be defended by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Since the 1980s, she has kept a lower public profile.

After retiring from performance and recovering from a stroke, she made a limited return to public life, appearing locally in southern California and giving interviews. In June 2016, she was honored at the 18th annual Trans Pride L.A. festival alongside CeCe McDonald.

Tracey ‘Africa’ Norman (1952 – present)

Black trans people have innovated and set trends in almost every industry, including the fashion world. Tracey “Africa” Norman, aka Tracey Africa, is an American fashion model, and the first Black trans woman model to achieve prominence in the fashion industry.

Originally from Newark, New Jersey, Norman has modeled and been photographed for such publications as Essence, Vogue Italia and Harper’s Bazaar India. Whether she knew it or not back in the 1970s, Norman paved the way for Black trans models today such as Jari Jones and Aaron Rose Philip.

Charley Burton (Unknown – Present)

There aren’t many trans elders over the age of 60 in Virginia, let alone in Charlottesville, but here is one Black trans man who deserves so many flowers:

Charley Burton, a 62-year-old Black Transmen Inc Board Member and a native Virginian, discovered his authentic self at the age of 50 and started his transition. September 13, 2010, is the day that Charley recognizes as a part of his emerging into his manhood. It was around that time that Charley was introduced to Carter Brown and became a part of the BTMI family. He has been active ever since.

Burton is the author of The Boy Beneath My Skin: A Black Trans Man Living in the South (2022). The book is about the many journeys that Charley has taken “to become the man that I am today.”

From a child born in a small rural town, who at the age of eight knew that he was different, to his path of recovery from drugs, alcohol, and food, and “moving into my transition from female to male,” this is a story of struggle, disappointment, and triumph. It is a story of “digging beneath my skin to become whole.”

As a BTMI founding board member, Charley loves the work that he does for his communities and loves what BTMI gives back to him. After transitioning, Charley has had a lot to say about how communities treat their transgender residents. He also wants you to know that the policies our elected officials enact matter.

Black Representation In Media

In his 1997 essay, “Remembering Civil Rights: Television, Memory, and the ’60s,” the media scholar Herman Gray lays out his theory of what was acceptable to show on network television:

“Black people portrayed in news coverage of the civil-rights and Black Power movements appeared either as decent but aggrieved Blacks who simply wanted to become a part of the American dream, or as threats to the very notion of citizenship and nation.”

For many white people, witnessing Black people of all genders and sexualities fighting for their rights felt like a threat to their power.

Despite decades of systematic attempts to discredit and dehumanize Black people in media, increasing Black cis, trans, and gender nonconforming representation has helped to shift public perception of Black lives and Black achievements.

Today in 2024, there is still a long way to go (#BlackLivesMatter and #Blacktranslivesmatter are still relevant hashtags) in our fight for equality and equity, but we are inspired by Black trans artists, entertainers, and other public figures who continue to make an impact today.

The Problem With Cis Actors Playing Trans Characters

The first-ever Black-White cisgender-transgender/TGNC “romance” was featured in The Crying Game (1992), starring actor Jaye Davidson, a Black mixed cisgender gay man, who plays transgender woman Dil.

This film doubled down on the on-screen transphobic trope of the deceptive trans woman who tricks the cisgender man, and what followed was relentless transphobic and anti-Black “jokes” on TV about this film for years to come (learn more about this in the documentary film DISCLOSURE).

Audiences wouldn’t see a Black trans woman consistently and authentically playing a Black trans woman character on any mainstream network or streaming platform until over a decade later, in Orange Is the New Black (2012-2019).

Black Trans Actors & Black Trans-Led Media

OITNB star Laverne Cox’s big breakthrough happened after years in the industry, when she was cast as Sophia Burset on the Netflix television drama. Cox’s character Burset, a transgender woman, is in prison trying to get hormone treatments.

For her performance, Cox was nominated for a Primetime Emmy in 2014, 2017, and 2019. After the show ended in 2019, Cox continued to take on acting roles in movies and on television. Her later credits included the films Charlie’s Angels (2019), Promising Young Woman (2020), and Jolt (2021).

A year after Laverne Cox appeared in the first season of Orange Is the New Black, Sasha Alexander

founded Black Trans Media & #blacktranseverything in 2013, which addresses the intersections of racism and transphobia by reframing the value & worth of Black trans people.

Sasha stands on the shoulders of Laverne Cox and Dr. Kortney Ryan Ziegler, who directed the independent film STILL BLACK: a Portrait of Black Transmen (2008); a collection of six short black-and-white films conceived during the years Ziegler was a doctoral student in the department of African-American studies at Northwestern University.

The film explores the theme of FTM transition in the Black community. Upon release to the queer film festival circuit, STILL BLACK: a Portrait of Black Transmen became one of the most sought after and talked about films representing the Black trans man experience, showing to sold-out crowds in cities such as Los Angeles, Toronto, Seattle, Chicago, and more.

Ziegler, Alexander, and Cox all stand on the shoulders of Janet Mock, a Black trans woman who began her transition as a freshman in high school, and funded her medical transition by earning money as a sex worker in her teens.

Mock earned a Master of Arts in Journalism from New York University in 2006. Her career in journalism shifted from editor to media advocate when she came out publicly as a trans woman in a 2011 Marie Claire article.

Mock’s memoir about her teenage years, Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More, was released in February 2014. It is the first book written by a trans person who transitioned as a young person, and made The New York Times bestseller list for hardcover nonfiction.

Another 2014 breakthrough: Angelica Ross, a Black trans actress, entrepreneur, and trans rights advocate (and self-taught computer programmer), founded TransTech Social Enterprises, a firm that helps employ transgender people in the tech industry.

Ross then began her acting career in the web series Her Story (2016), after which she received critical acclaim for her starring roles in the drama series Pose (2018–2021) and the anthology horror series American Horror Story (2019–present). Ross is the first trans person to star in two season regular roles, consecutively.

D. Smith, a Black trans producer and director, had a banner year in 2023. She has produced for LilWayne, Andre 3k, Fantasia, Billy Porter, Ciara, Estelle and more, and her documentary Kokomo City will be available on Paramount Plus on February 2, 2024.

The Academy Award contender is D. Smith’s directorial debut, following four Black trans sex workers, Daniella Carter, Koko Da Doll, Liyah Mitchell, and Dominique Silver, in Atlanta and New York City.

The documentary made its world premiere at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival and took home two awards. Further on, it was nominated for a Film Independent Spirit prize for Best Documentary and went on to win the audience prize in the Panorama Documentary section of the Berlin Film Festival.

More Black TGNC Representation At Sundance

As the 2024 Sundance Film Festival kicked off, Imara was joined on TransLash Podcast by the creators of last year’s award-winning documentary, The Stroll. Imara spoke with co-director Kristen Lovell, a Black trans woman, about why she began to document her experience as a sex worker on the stroll and how she’s learned to navigate the world of prestige film festivals and studios.

The Stroll explores the history of New York’s Meatpacking District from the perspective of the trans sex workers who lived and worked there. Lovell recently shared with the Los Angeles Times the satisfaction she gets from entering pre-production on a new project:

“One thing that never ceases to amaze me is the joy of uncovering new elements of stories that I was not previously aware of. It’s in these moments that I realize the power of storytelling to connect people, shed light on the unexplored and bring hidden narratives to the forefront.”

At the Seeking Mavis Beacon world premiere at Sundance 2024 on January 20, we asked director Jazmin Renée Jones (she/they) why there was so much beautiful imagery of queer and trans lives in her feature debut about the mysterious Black woman behind the avatar in the iconic 80s typing software Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing. This was their response:

“As a Black, queer, non-binary filmmaker, there’s no question that this is a Black film. It’s just, it’s Black cinema. Me being Black, regardless of what the subject of my film is, it’s a Black film. And I think it’s really interesting that queer cinema, it’s a little trickier. And it’s like, I think this [their film] is queer cinema. Olivia and I are gay as hell, but but it’s like absent of a love plot. It’s like we don’t qualify. And I think queer cinema is also just like, hey we’re queers, we’re out here.”

Black Trans Politics & Activism

In 2017, three Black trans women founded Compton’s Transgender Cultural District in San Francisco, CA; the first legally recognized transgender district in the world. This achievement paved the way for cities worldwide to examine and improve upon how local government and media supports and represents Black trans residents.

Originally named after the first documented uprising of transgender and queer people in United States history, the Compton’s Cafeteria Riots of 1966, the district encompasses 6 blocks in the southeastern Tenderloin and crosses over Market Street to include two blocks of 6th street.

In 2016, the City of San Francisco renamed portions of Turk and Taylor to commemorate the historic contributions of transgender people, renaming them “Compton’s Cafeteria Way” and “Vikki Mar Lane” respectively. January 31, 2022, marked Compton’s Transgender Cultural District‘s five year anniversary. Check out Transgender District’s list of Black trans pioneers here.

A year after the launch of Compton’s Transgender Cultural District, TransLash Media founder Imara Jones, a Black trans woman, released the first in a series of Black trans-affirming short documentary films entitled TransLash Episode 1: Transitioning Genders in Trump’s America (2018).

The documentary series was the catalyst for Jones’ platform TransLash Media (2019-present), a nonprofit news organization and community platform that tells trans stories to save trans lives, all while documenting TGNC lives through a Black trans lens.

In 2021, two Black-trans led orgs focused on technology and trans advocacy overlapped in a beautiful way: TransTech Social Enterprises and TransLash Media were beneficiaries of Pride Live‘s Stonewall Day 2021 fundraising initiative. Folks could text REBEL to 243725 to donate funds to TransLash Media and TransTech Social Enterprises during Pride Month (watch the livestream replay here).

While TransLash Media isn’t a policy or governmental agency, in 2023, TransLash took The New York Times to task for the anti-trans bias in their reporting on LGBTQ+ bills, via TransLash’s Season 2 of the #AntiTransHateMachine podcast series and the companion animated series:

In a 2023 statement from the New York Times shared with TransLash Media, they continued to defend their reporting on trans issues, saying the paper has published hundreds of articles “specifically on discrimination against transgender people and/or anti-transgender legislation since January 2020.”

However, TransLash’s extensive analysis of New York Times coverage of trans issues, led by Imara Jones, found disinformation and anti-trans pseudoscience to be regularly elevated in these articles without correction or context.

As of press time in January 2024, TranLash Media has yet to receive a response from the New York Times about their contradictory statements.

Here are some resources to find more Black trans leaders and Black trans-led organizations to support:

- 📖 Andrea Jenkins is an American politician, writer, performance artist, poet, and transgender activist. Jenkins made history in 2017 as the first Black openly trans woman to be elected to office in the United States.

- 📖 Phillipe Cunningham, a Black trans man and another Democrat on the Minneapolis City Council, lost his bid to represent Ward 4 for a second term in 2022, but his impact continues today.

- 📖 Mauree Turner is an American politician and community organizer. A member of the Democratic Party, they have served as a member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives since 2021. Turner is the first publicly non-binary U.S. state lawmaker and the first Muslim member of the Oklahoma Legislature.

- 📖 Stanley Martin, a Democrat who won a city council seat in Rochester, New York, in 2021, joins the shortlist as one of the country’s few Black trans and nonbinary elected officials.

- 📖 This list by Raquel Willis is an evolving, community-sourced list of organizations and initiatives that are led by and/or predominantly serve Black transgender, gender nonbinary (NB), and gender-nonconforming (GNC) people.

- 📖 Watch The Future of Trans (2020) to learn about even more Black trans leaders.

Black Trans Lives: 2022 and Beyond

Black transgender people can see themselves onscreen more than ever before, which is encouraging after decades of erasure.

POSE (2018 –2021), set during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York City, is a groundbreaking series that depicts NYC Ball culture in the late ’80s, early ’90s. The television series premiered on June 3, 2018, on FX. Janet Mock was a writer, director, and producer on the show, and was the first Black trans woman hired as a writer for a TV series in history.

POSE boasts multiple Black & Afro-Latinx transgender/TGNC actors, including Mj Rodriguez (Blanca Rodriguez-Evangelista), Indya Moore (Angel Evangelista), Dominique Jackson (Elektra Abundance), and Angelica Ross (Candy Abundance/Ferocity).

On July 13, 2021, Mj Rodriguez made Emmy history by becoming the first trans lead ever nominated for Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress In A Drama Series.

While it’s wonderful to see more expansive, prismatic representations of Black cisgender and TGNC people in media, Black transgender and gender nonconforming people still face some of the highest levels of discrimination of all transgender people.

Despite the many painful and frustrating statistics, we at TransLash Media continue to focus on all of the healing, innovation, and positive transformation that Black trans people steward across industries and in politics.

In 2023, Translash Media in association with the WNET Group’s Chasing the Dream Initiative, released the second and third installments of American Problems, Trans Solutions, a docuseries detailing the contributions of Black trans community leaders working to solve pressing issues in their communities across the country.

The docuseries features some incredible Black trans leaders and visionaries:

- 👑 Kayla Gore, Executive Director of My Sistah’s House, an affordable housing advocate in Memphis, TN;

- 👑 Breonna McCree, Co-Executive Director of The Transgender District, who helps trans people start and build businesses in San Francisco, CA;

- 👑 Oluchi Omeoga, Co-Director of the Black LGBTQIA+ Migrant Project in Minneapolis, MN, who is building a support network queer Black immigrants and refugees.

Indya Moore (they/them), a trans non-binary Bronx native who identifies as Afro-Taíno, is known for their creative talents and insightful views on topics of gender, race, class, mutual aid, the arts, and more.

The Pose star shared their refreshing wisdom at the world premiere of River Gallo-penned and produced Ponyboi at Sundance 2024. During the Q&A, Moore—who plays Charlie in Gallo’s intersex-affirming & Jersey-set thriller—complimented cis director Esteban Arango on being incredible due to his emotional intelligence.

Black trans people have always been here, and during Black History Month and every month, we honor our collective histories to inform the future we are creating together; one that is a safe and affirming place for all trans, intersex, two-spirit, and gender nonconforming people and those who love them.

Black Queer & Trans History Reading List

Here are some Black trans & Black LGBTQIA-affirming books to add to your collection during Black History Month and beyond. Did we miss anything? Let us know and we’ll update the list!

- 📖 The Echoing Ida Collection (2021) by Cynthia R. Greenlee (Editor), Kemi Alabi (Editor), Janna A. Zinzi (Editor), Michelle Duster. Founded in 2012, Echoing Ida is a writing collective of Black women and nonbinary writers who—like their foremother Ida B. Wells-Barnett—believe the “way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” Their community reporting spans a wide variety of topics: reproductive justice and abortion politics; trans visibility; stigma against Black motherhood; Black mental health; and more. This anthology collects the best of Echoing Ida for the first time, and features a foreword by Michelle Duster, activist and great-granddaughter of Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

- 📖 Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (2017) by C. Riley Snorton

- 📖 Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility (2017) by Reina Gossett (Editor), Eric A. Stanley (Editor), Johanna Burton (Editor)

- 📖 A Finer Specimen of Womanhood: A Transsexual Speaks Out by Sharon Davis (1986). With the publication of A Finer Specimen of Womanhood, Ms. Davis became the first Black trans person to publish a memoir. This unprecedented work is no longer in print and difficult to find, but those interested in her life can find a lovely profile in a 1983 issue of Jet available from the magazine’s online archives.

- 📖 FIRE!! a Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists (1926). Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Wallace Thurman, Aaron Douglas, Richard Bruce Nugent, Gwendolyn Bennett and John P. Davis created FIRE!!. The publication reads as a love letter to the young queer Black community, replete with poetry, plays and short stories. Only one issue was ever made. Read FIRE!! online for free, thanks to POC Zine Project.

- 📖 TransLash Zine (2019-present) is an independent publication that centers Black trans & BIPOC trans voices, along with non-Black trans allies. Purchase hard copies here and read online for free.

Before you click away, this episode of TransLash Podcast with Imara Jones is a must-listen!

Did you find this resource helpful? Consider supporting TransLash today with a tax-deductible donation.