|||||

"Everyone will benefit from learning the connections between trans and autistic experiences and identities..."

by Zel Amanzi

Growing up, I was a Russian nesting doll, missing every layer but the tiniest figurine and the outermost shell. I slowly lost access to my innermost being as I spent most of my energy trying to figure out what made me so different. Well into adulthood, I semi-existed in this expansive gap between who I was and how people saw me. Eventually, I learned to turn myself off and mimic those around me.

I would pray to God to make me a boy, but I resigned to the belief that God made me a girl because it was the best of two bad options. As puberty struck, my theory fell apart. The sensory experience of estrogenic development was hell and it never got better. At some point I heard the word “queer,” and it was like another layer suddenly appeared. At 26, I heard the term “non-binary,” and boom: I identified the next layer. I realized for the first time ever that I might one day feel whole.

This process, which I now understand as embodiment, continued as new words and phrases emerged: non-monogamous, PTSD, agender, animist. Yet, a gap still existed between the tiniest doll at the core, and the rest of me—that is until I was diagnosed with ADHD at 32 and encouraged to begin assessments for Autism. During that process, my body felt like a domino artist had just carefully toppled the first piece in an elaborate setup; the cascade ensued, and with each falling piece, every single memory and experience in my life began to make sense. I finally connected every layer of the set. Only then could I really articulate—to myself—what all of my other identities meant, especially being nonbinary and transgender.

As I came to realize, transgender and autistic identities are widely misunderstood. This misunderstanding often stems from a lack of access to accurate information. There is also a misguided belief that transgender and autistic people are exceedingly rare, rather than inaccurately represented. These narratives come from a stubborn commitment to pathologizing differences and violently suppressing them as “threats.”

So what do the words autistic and transgender mean? Transgender people are people whose physiological, psychological, spiritual, and emotional experiences do not align with their binary sex assigned at birth. The gender binary is an easily-disproved social construct in which only two genders exist, and they are inextricably tied to two specific combinations of genitalia, reproductive organs, hormones, and chromosomes. It then prescribes “acceptable” social and sexual choices based on these two combinations.

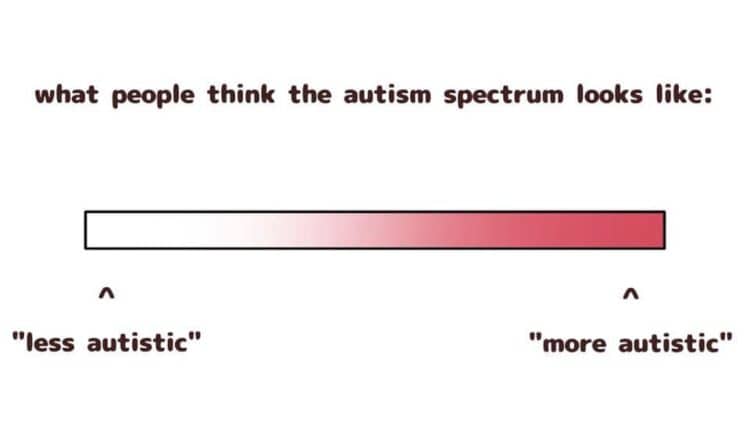

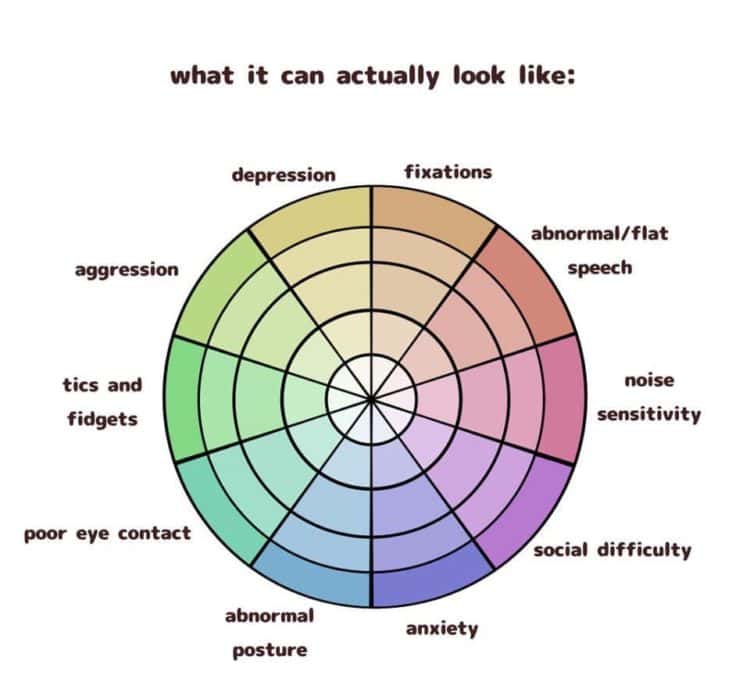

Autistic people are people whose sensory, neurological, and communication patterns differ from what decision-makers (typically psychiatric and educational gatekeepers) consider socially typical or compliant. Autism lumps together a wide variety of behaviors and conditions related to the brain, the nervous system, and communication—some more obvious and disabling than others—which are collectively referred to as a neurotype. Autism is often described as a disorder, but most autists in the growing popularity of the neurodiversity paradigm argue that likening autism to a disorder is a product of the same constructs that uphold the gender binary. However, just as sex, gender, and body diversity exist—neurological diversity does, too. These are biological facts, not opinions. Yet, transgender and autistic identities are often used to deny the reality of human diversity rather than explore it.

Unfortunately, transgender and autistic realities are often treated as matters of opinion rather than facts of humanity. This fuels narratives, research, and legislation that describe transgender and autistic existence in eerily similar ways. They emphasize mental deficits, social misery, inconvenience to disappointed parents, dramatic behavior, and inability or refusal to conform as justification for denying medical and bodily autonomy. Stories and representations of transgender and autistic people have been unhelpfully co-opted by people who don’t hold these identities. Angry novelists and comedians like JK Rowling and Dave Chapelle devote their media rants to vilifying transgender people by misusing feminist and racial liberation theories. Mothers of autistic children nonconsensually upload videos of their children in extremely sensitive emotional states and inappropriately define autism by their own intolerance for parenting.

Meanwhile, misinformed people incorrectly link vaccines to autism, and geneticists publish papers identifying “autism genes” with the express purpose of eliminating autistic people from existence. Accurate depictions of autistic and transgender experiences are hard to find. Oftentimes, when we do see autistic and transgender representation, the narrative serves the comfortable illusion of normalcy that protects cisgender people (people who are not transgender) and allistic people (people who are not autistic) from the winds of difference.

Everyone will benefit from learning the connections between trans and autistic experiences and identities: Transgender and autistic people, as well as the families, doctors, therapists, and teachers who often willfully misunderstand them. The everyday lives of transgender and autistic people are dominated by a social experience of surviving in a world that overwhelmingly denies the validity of their internal experiences and justifies subtle, egregious violence against them. Just as many queer people have been historically subject to non-consensual “corrective” therapies, many autistic people must survive programs like ABA (Applied Behavior Analysis) whose definition of success requires “correcting” their natural tendencies. Some institutions still advocate for electroshock punishment for autistic children and refer to this child abuse as therapy. Legislators in Texas now threaten parents and doctors with child abuse charges if they provide life-saving healthcare to transgender children. These dystopian realities reflect how essential bodily autonomy, medical autonomy, and human diversity are to both transgender and autistic advocacy, especially in formal research and diagnostics.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a highly influential insurance coding and billing manual. In its 5th edition, the DSM changed the required diagnostic code for gender-affirming medical care from “Gender Identity Disorder” to “Gender Dysphoria.” Dysphoria emphasizes internal sensory experiences rather than distance from social expectations. This allows transgender people to define themselves for themselves rather than for the parents and service providers who judge them as abnormal. Hopefully, formal labels for “Autism Spectrum Disorder” might see similar changes when research and media begin centering autistic lived experiences instead of parent and educator discomfort. Maybe then, society at large will realize that those people in their life they euphemistically label as “quirky,” “picky,” “weird,” and “special” not only deserve to be understood, but can also be welcomed into communities that will love and accept their differences.

Ultimately, both autism and transgender identities are internal experiences that turn social conformity into a sensory burden that strains the nervous system. Both communities have a relationship to their bodies that challenges social expectations. This non-conforming sensory processing is not limited to the brain, as brains are attached to a nervous system that receives information through our eight senses and communicates with our entire bodies. Life in these non-conforming bodies is often the primary lens through which many transgender and autistic people experience their senses of Self.

And those bodies? They exist in a society that tells us our very sense of Self and our value as members of society depends heavily on our gender. How many people are asked not what kind of person they want to be when they grow up, but what kind of woman or man they want to be? Autistic and transgender people know viscerally that few socially acceptable responses to those questions actually exist. So, is it any wonder that people with an atypical bodily-sensory experience might often express their identity differences in the language of gender?

Transgender and autistic people often find themselves obligated to explain their existence as legitimate expressions of human diversity. Therefore, both communities spend a great deal of energy deconstructing the relationship between bodies, communication, and identity. Consequently, both communities tend to be highly aware of the arbitrary social rules dictating “realness” and safety. This often results in “masking” or the hiding of one’s true self for survival. Unfortunately, too few trans and autistic people are able to connect their inner and outer expressions as I did. Masking saved my life, but at the expense of my mental health. That life-long distress could have been dramatically reduced by receiving affirmation rather than constant correction. I often wonder how differently the DSM would describe these experiences if professionals acknowledged the impact of this survival process without blaming us for it. Understanding the foundations of neurodiversity and gender diversity as inextricably linked to sensory processing can help many trans and autistic people shift from surviving to thriving. It can help service providers create support frameworks that do not rely on the very tactics that cause distressing symptoms in the first place. It can help families stop harming the children they are supposed to honor. Researchers who do acknowledge these sensory patterns have demonstrated meaningful connections between gender and neurodiversity: Autists and people with ADHD are more likely to identify as queer and/or gender non-confirming; similarly, transgender people exhibit autistic traits at higher rates than cisgender people. Identity terms describing these combined experiences, such as “autiegender” and “nueroqueer” reveal how natural these connections can be. Many autistic and transgender people view their experiences both as a spectrum and as an identity that cannot be separated from who they are.

These identity spectra are not linear for either group. If you spend enough time on the #actuallyautistic side of social media, you’ll find a pie chart in which each triangular section represents various autistic traits including sensory hypersensitivities, intensely euphoric or dysphoric bodily sensations, empathy, increased pattern awareness, critical thinking, social anxiety, atypical body movement, creativity, atypical communication, and many more. Each section is colored in to varying degrees to indicate which of these experiences are the most present. Each autistic person will have a different pie chart. Then, take a closer look at those traits. Consider how many also apply to transgender people. Anyone who has had the privilege of loving or living as a trans person knows the answer is, “a lot!” Rates of physical and social dysphoria, mode of expression, and desire to “fit in” dramatically vary amongst transgender people. Of course, every transgender person would also have a different pie chart. But one thing is for sure—we all have non-dominant bodily-sensory experiences that determine how we see ourselves and how we experience the world.

In this world where people in positions of power use difference as an excuse to institutionally abuse transgender and autistic people, it is essential that we direct formal research and casual self-education toward building connections between various types of difference. When we do this, we can develop language to effectively communicate basic truths about what it means to be a person and a society. This includes the fact that every single one of us is different, whether we feel the need to label it or not. Some people just happen to be different in ways that society refuses to support, while others can more easefully suppress their differences to conform to society. Transgender and autistic people, whose differences are rooted in sensory experiences and therefore lead to nervous system distress when ignored, can’t conform to society’s expectations without serious mental health consequences. But what if that does not mean that they are broken? What if it instead indicates that a society that cannot accommodate the full truth of humanity—that will not accommodate the full spectrum of its citizenry—is actually what needs fixing?

Featured image by Eva Almqvist.

Zel (they/he) is a multiply-neurodivergent and agender transbeing. Other identities include writer, hobby gardener, and obsessive typewriter collector. Formerly a classroom teacher and food sovereignty organizer, they now integrate their M.S. Ed in Social Justice Education and various certifications in energy work as a counter-colonial Sacred Energy Educator. In addition to writing for Translash, Zel is the founder and director or Transgressive Medicine, teaches with Transgender Training Institute and CutiesLA, and is a co-founder of Trans Yoga Project.

Resources

- TransLash Guide: Resources For Trans People On The Spectrum

- Radically Open Dialectical Behavioral Therapy: What Is It And Is It For Me?

- Trans-Affirming Mental Health Resources

Did you find this resource helpful? Consider supporting TransLash today with a tax-deductible donation.